John C. Copeland, VP/COO • Energy Assurance LLC

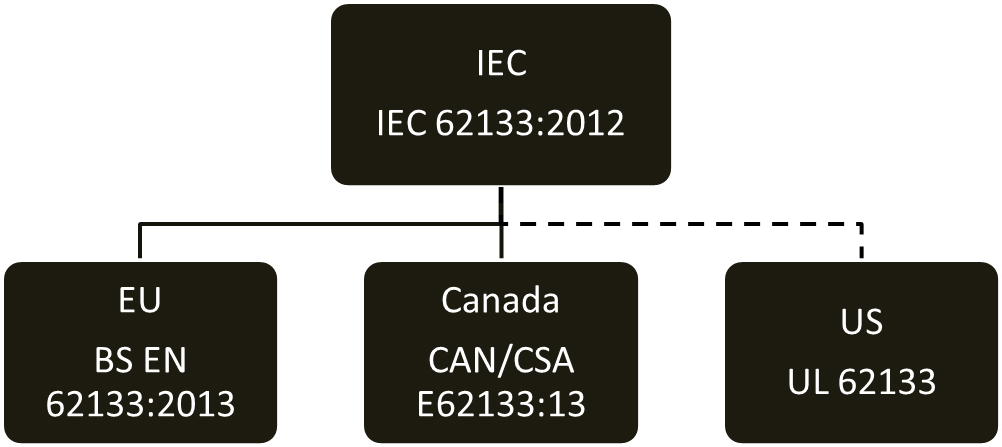

Although not widely publicized, Underwriter’s Laboratories (UL) released a new battery standard applicable to rechargeable lithium cells and battery packs in early January 2015. This standard, UL 62133 (Revision 1), takes its place among other country-specific versions of the IEC 62133 international standard which has been in active use for global battery approvals for many years. Why is this important? After all, do we really need another battery standard? As it turns out the answer is a definite “Yes” and is driven by a single concept – Harmonization.

For many years the applicable cell and battery standards for certain approvals in the US were UL 1642 and UL 2054 respectively. Although these are well-established standards that have been revised over the years, they lacked commonality with testing done globally. The net effect was that companies needing certain US approvals for the devices that the batteries powered were required to test the cell and battery to IEC 62133 internationally while also obtaining testing to UL 1642 and UL2054. The advent of UL 62133 begins the process of reducing that test burden.

As released, revision 1 of UL 62133 is fully harmonized with IEC 62133. To be completely clear, it is an exact copy of the current IEC standard. The only exception is that following UL’s normal practices, the UL version of the standard requires that safety critical components are 3rd party certified. Furthermore, it has been suggested that UL 62133 may eventually replace UL 1642 and UL2054. This is a particularly significant change given the differences in approach between the two options.

So how different are they? Most significant is that UL 2054 employs two test concepts that are conspicuously missing from the 62133-based family of standards:

Single Point Faults: Many of the electrical abuse tests in UL 2054 required that modifications be made to disable portions of the battery pack’s protection circuitry. Most commonly this involves the following but depending on the design of the protection scheme, other faults may be specified:

- Adding a short across the charge or discharge field effect transistor (FET). FETs are used as switches to stop the flow of current in over-voltage, over-current and under-voltage conditions.

- Fixing the polarity of the charge or discharge FET’s gate. Essentially this prevents the FET from stopping the flow of current. Unlike the short noted above where the current flows around the FET, this fault forces all of the current to flow through the FET.

- Adding a short across the sense resistor. Sense resistors are used to assess how much current is flowing in or out of the battery. Shorting out the resistor causes an incorrect reading of current and thus may impede a proper response by the protection circuit.

- Shorting the outputs of the protection integrated circuit (IC) that drive the gates of the charge and discharge FET. This has the effect of sending sometimes unpredictable signals to the gates of the FET once again impeding any response to a detected fault condition.

Worst Case Operating Point: In the trade, this is referred to as “trip/no-trip” testing. In addition to implementing single point faults, load testing is done to determine the maximum amount of current that will not cause the circuit to rapidly cease operation. Put another way, the goal is to find the point where the faulted circuit trips and run the testing just below this so that the maximum stress is applied to the device under test. Note that each fault type specified for a given test must be individually load tested to find this worst case operating point as it will vary by fault.

Some have argued that such a testing approach really involves three levels of faults combined. Consider first that the testing itself constitutes abuse that only occurs when something external to the pack has deviated from normal operation. Examples include shorting the output, overcharging the input, applying thermal stress and creating cell imbalances in series circuits. The second level is the direct application of intentional faults into the battery’s protection apparatus. Finally, the third level is running the test at the highest operating current such that the resulting stress is maximized.

Creating this perfect storm of stresses requires significant time and skill on the part of the certification laboratory and thus commands increased test costs and extended test durations. Many have commented that the likelihood of such a combination of negative events in actual field performance is remote at best, and thus have questioned the real value of taking the testing to such an extreme. The corresponding opposing argument is that such testing permits assessment of the inherent safety of the battery when its primary protection capabilities are removed. A final note is that although fault testing is commonly done in many electrical safety standards, it is not a common practice in the vast majority of existing battery standards.

UL 62133 does not involve faulting or worst case operation. Instead it is focused on abuse cases applied to the cell or battery as it would be found in actual application. This means that the safety circuit and any other protection devices are not disabled during electrical abuse testing. Criteria vary by test, but a passing result is characterized by “No Fire/No Explosion” in a majority of cases. Mechanical abuse testing is limited as the current revision draws a majority of its physical compliance from ensuring that UN 38.3 lithium cell and battery transport testing was successfully accomplished. Actual repeat testing is not required as a certificate of compliance is considered acceptable evidence.

|

Cell Tests |

Battery Pack Tests |

|

Continuous Charging (7 days) External Short Circuit Free Fall Thermal Abuse Crush Forced Discharge |

Moulded Case Stress External Short Circuit Free Fall Overcharging of Battery |

UL 62133 Tests by Cell and Battery Pack

Requirements to test cells and batteries are generally driven by the certification requirements for the devices that they power. Given this, what are some of the most common end device standards used in the US and what do they require in terms of cell and battery testing?

| End Product Type Category | Applicable Standards |

| Information Technology Equipment (ITE) | UL 60950-1

UL 62368-1 (Risk Based) |

| Medical Equipment | UL 60601-1

ANSI/AAMI ES60601-1 |

| Measurement, Control, & Laboratory Equipment | UL 61010-1 |

End Product Categories and Corresponding Standards

Information Technology Equipment (ITE) is currently in the midst of a transition between the traditional objective testing found in UL 60950-1 and risk-based testing as outlined in UL 62368-1. A positive sign is that both standards have been aligned to two distinct options for cell and battery compliance. The traditional option of having the cell certified to UL 1642 and the battery pack certified to UL 2054 with a complimentary certification to UL 60950-1 is still a valid approach and continues to see frequent use. To some degree this is driven by the reality that most lithium cells are certified to UL 1642 as a matter of course by their respective manufacturers, thus there is a large variety of pre-existing certified cells. Equally viable is to obtain a CB report to IEC 62133 (this includes both the cell and battery) and then conduct the battery related testing on the end device to the requirements found in Annex M of UL 62368-1. These tests in Annex M are tailored to explore from a safety perspective how the end device handles battery faults. It is expected as more cells are certified to IEC 62133, this option will continue to gain favor. With UL 62133 being harmonized to IEC 62133, converting an existing IEC 62133 CB report to UL 62133 should be a relatively simple administrative matter and may not involve additional testing.

For medical devices falling under the 60601-1 standards, the requirement is that lithium batteries are required to comply with the 60601-1 standard itself and meet nationally recognized standards or internationally harmonized component standards. The latter portion of that statement governing component requirements does not preclude the use of UL 1642/UL 2054, IEC 62133, or UL 62133.

The equipment standard (61010-1) is even more general. It only specifically says that lithium batteries must meet the safety requirements of the standard itself. It does not go the additional step of calling for compliance to component standards. Despite this, the common practice employed by many certification organizations is to look for such compliance. In the past it was UL 1642 and UL 2054, but it is suggested that either IEC 62133 or UL 62133 are also valid options. What is actually required in practice is generally left to the discretion of the certification body’s responsible engineer thus advance consultation between product designers and their certification organization is prudent.

So far we have discussed the current state of the UL 62133 standard as released, how it compares to the existing UL 1642 and UL 2054 standards, and how it is expected to operate in conjunction with end product standards. What does the future hold for UL 62133? To answer that question, one must first note the upcoming changes to IEC 62133. This standard will be spitting into two separate standards in August of 2016. IEC 62133-1 will be specific to nickel chemistries, whereas IEC 62133-2 will cover lithium chemistries.

Additionally, vibration and mechanical shock testing that was originally removed in favor of providing evidence of compliance to UN 38.3 is being reintroduced. Finally, faulting is being introduced, but at this point is only being included as a best practice that should be considered as opposed to an explicit requirement for compliance. It is fully expected with certainty that UL 62133 will follow suit in terms of splitting along chemical lines and readopt the noted mechanical testing. Faulting and possibly worst case operation are being discussed for inclusion, but at this point it is unclear if they will remain as best practice recommendations or become mandatory compliance requirements formally documented as a US national deviation.

So where does this leave product designers as of today? For now, it is important to realize that another option for cell and battery compliance may exist for their product via UL 62133. Depending upon the guidance provided by their certification body’s compliance engineering staff, the more common end product standards seem to allow the use of UL 62133 as an alternative to UL 1642/UL 2054. Again, situation dependent, this may offer lower test costs and shorter test durations subject to the availability of approved cells. At this time, UL 62133 is fully harmonized with the existing international requirements as stated in IEC 62133, but the future still holds some uncertainty. The topics of faulting and worst-case operation are still undecided for UL 62133, but should start to move to resolution as the August 2016 release date approaches for the new revisions of IEC 62133.

|

UL 1642 / UL 2054 |

UL 62133 |

| Not internationally harmonized | Harmonized to IEC 62133 (can get a CB report) |

| More component tests | Fewer component tests |

| Faulting and worst-case operation required | No faulting or worst-case operation |

| 80-170 cells and 55 battery packs required | 45-55 cells and 21 battery packs required |

| Accepted by end product UL standards without additional testing | Requires additional end-device testing involving the battery pack for ITE products |

| Many cells certified to UL 1642 already | Few cells currently certified to UL 62133, although many have been tested to IEC 62133 (conversion required for certification) |

| Longer test duration | Shorter overall test duration |

| Higher test costs | Lower test costs |

Summary comparison of UL 1642/UL 2054 and UL 62133

Energy Assurance utilizes an extensive knowledge of batteries and testing to provide the battery industry with a comprehensive, forward-looking and responsive testing resource to help clients mitigate risk. We are an accredited battery testing lab with certifications from TÜV SÜD, Underwriters Laboratories, ACLASS and IECEE. For more information, contact Energy Assurance.